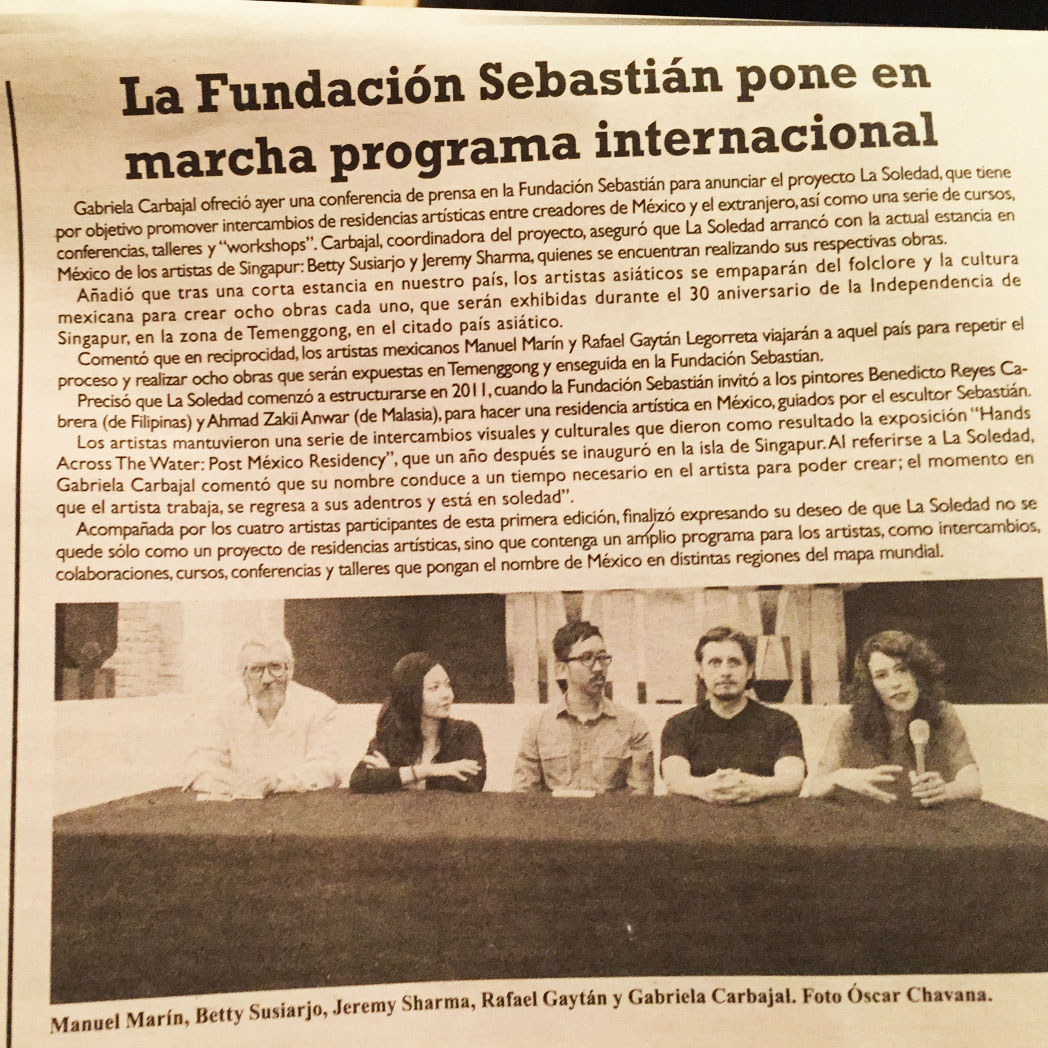

Singapore-Mexico Cross-Cultural Exchange: A Post-residency exhibition

Shimmering Surfaces:

Reflections on Cultural Exchange

The cultural legacy of Mexico has always the subject of fascination, stretching far beyond the five hundred years and more since its conquest by the Spanish. And while Mexico has, in part, achieved a modernization in all aspects of contemporary urban life; the visible presence of this rich legacy in contemporary culture and society is clearly evident to the outsider. However, the hazards of this allure of the past, exacerbated by the tourist industry seeking to promote a form of exotic cultural difference, are well known. As such, the ability to able to capture this legacy in contemporary terms has long remained a challenge for foreign writers and artists. Nonetheless, arguably, cultural exchange and engagement between cultures remain important forms in strengthening the understanding and appreciation of each other.

Mexico has been a favorite country for artists to travel to through the course of its colonial and modern history. This provoked tremendous cultural exchange at times. The contrast between Mexico and Singapore could not be more vivid, a country barely fifty years old and the other well over 500 years. Both Betty Susiarjo and Jeremy Sharma of Singapore visited Mexico briefly as part of an exchange program between the two countries and the impact is palpable. In this project of exchange with Mexico, gold momentarily unites these two artists of Singapore. Both artists use gold as emblematic of Mexico and its cultural heritage, stemming back to its pre-Hispanic use and period of Aztec rule.

The Aztecs had been a Mesoamerican people of central Mexico from the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries. The nucleus of the Aztec Empire was the Valley of Mexico, building their capital upon raised islets across Lake Texcoco. The 1521 conquest of Tenochtitlan by Spanish forces and their allies brought about the effective end of Aztec dominion and the founding of a new settlement named ‘Mexico City’ on the site of the now-ruined Aztec capital. Some historians have called it an ethno-environmental conflict. a conflict waged by the Spanish and Europeans who destroyed the Aztec Empire and its land in pursuit of gold.

Even though gold in Mexico was not as extensive as down along the Western region of South America: Colombia, Ecuador or Peru, it was still highly valued within Aztec culture. In fact, the scarcity of gold gave it an even greater value. The Aztecs and those before them were civilizations with rich and long cultural traditions and for them gold was one of the most precious valued material for its shimmering, shining quality and used ceremonially. It was not only non-corrosive but malleable and could be moulded into ornate objects of worship and ornament. But gold was equally valued by Europeans not only for its ornamental quality, but as a sheer precious metal. Gold was much sought after during the years of conquest and became part of the emblematic signature of prestige, of royalty and fortune. Gold bars were made and greatly valued, holding their monetary value over time.

Of course, we must acknowledge too the use of gold in different cultural histories such as the extraordinary Golden Buddha of Wat Traimit in Bangkok. But the use of gold in the history of modernism is rare, except for such artists as Gustave Klimt and Yves Klein. Their use of gold as allegorical in Klimt and alchemical in Klein recall two traditions that have informed Western art.

Klimt used gold leaf in a number of his paintings from the first decade of the twentieth century. Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907) is a notable example, inspired not only by the sitter herself but equally, Klimt’s visit to the Byzantine mosaics at Ravenna, Italy in 1903. Upon his return to Vienna, he began to work in what became known as his “Golden Style” incorporating gold elements into both his allegorical and his portrait paintings. In this painting, Klimt used gold in a variety of ways, from the lustrous background to the shining fabric of Adele’s gown. The subject seems to become one with her glowing surroundings, yet a distinctive figure emerges from the profusion of decorative motifs. From 1949 on, gold for Klein represented materiality as a source of light, endowed with a driving force. He spoke of life as the “physical quality of the illumination of matter.” But it would take another ten years or so before he brought this matter into his work in the form of a Monochrome, the Monogolds, that is to say a “living matter” that ensures the passage from the visible to the invisible. Composed of gold leaf on wood, Le Silence est d’or (Silence is Golden), (1960) is a prime example of a a gold painting by Klein. When he exhibited a first ‘Monogold’ in early 1960, Klein publicly reintroduced multiple colours into his work. The Monogolds went beyond the realm of sensibility into that of artistic alchemy. Matter of exchange, transmutation and absolute desire, gold alone had the artistic qualities to transform an object into an artwork. Often the Monogold paintings were composed of two distinct gold substances: gold leaf smoothed over wood to form a base, and in relief to depict coins, as seen in Le Silence est d’or. This dual aspect of gold points to the breadth of its powers. As a currency of exchange, gold stood for the promise of eternity. Gold, Klein once said, “impregnates the painting and gives it eternal life.” Gold is the matter that leads to immateriality.

The exhibition presents new work by both Betty Susiarjo and Jeremy Sharma as a result of their visit to Mexico. They come out of distinct cultural heritages. Susiarjo born in Indonesia, emigrating with her family to Singapore at the age of fourteen while Sharma was born and educated in Singapore. And, both currently teaching at the prestigious LASALLE College of the Arts in order to sustain their practice as artists.

Betty Susiarjo has been well recognized for her involvement in community art work, perhaps to the expense of her own practice. But this has changed over the past year as she returns more and more to the development of her own practice. Three years ago, Susiarjo wrote of the experience of Beauty as “inspired by close observations of the everyday,” seeking through her practice to overcome what she sees as the “rivalry between nature and man, the landscape and the city, the organic and artificial, the dreams and the reality we live in.”

Susiarjo’s current work in the exhibition, the result of her short residency in Mexico, is an installation in five parts. First, there is a wall piece, composed of a golden chain suspended across the wall, from which hang small objects, including ‘milagros’ and black obsidian stones, over which is written a phrase from the great Mexican writer and poet Octavio Paz “you were all birds, and now you are a star.” Secondly, on the floor is a pyramid-shaped cone made of gold painted wood and thirdly, three brass fans, open and suspended on the wall. Fourthly, five pieces of cotton-embroidered pieces with designs adapted from Aztec patterns found on the internet and adapted by the artist, framed and hung on the wall. And fifthly, two projected videos of the streets at night in Mexico City and in Singapore. The image is composed of a maze of lights, both street lamps and car headlights, projected onto two panels made of gold and the other of silver thread. These videos shots offer a serendipitous moment of exchange between the two cities. The artist was not able to take a long shoot in Mexico and while inspired by the street nights of Mexico, they were reshot in Singapore. It is as if these lights (of streets and cars), which were an early symbol of modernity, unify the two cities.

There is an attentiveness to observing simple structures and forms and as such the latency of meaning within them. Nothing grandiose nor imposing but more in the form of visual poems where the shape and form, colour and line dance lightly across surfaces evoking more atmosphere and mood of beauty, of a lightness in seeing the world. To this degree the work recalls the post-impressionist artists such as Seurat, where again the lightness of touch, of color and form captures the beauty and effervescence of nature. This has been seen already in Susiarjo’s earlier video projections of 2011/12 where the flickering images of the sea, of nature, of passing objects capture a beauty that is, nonetheless, filled by a sense of their impermanence and frailty. And yet they are there, lustrous, illuminated, captured in the passing light.

Jeremy Sharma offers two works of three pieces each. The first entitled ‘Empires’ is composed of three panels 1.8 m. high, made of gold-colored patterned surfaces from mirror acrylic. Each of the three pieces is composed of nine vertical pieces. “They are basically pictures of infinity in two ways – expanding of space through mirroring and reflection and the expansion of a motif into a pattern inspired by the mathematical idea of fractals through design, geometry and ornamentation.” The design is influenced by latticework found by the artist on the internet that correspond closely with the kind of designs found in traditional Mexican ceramic tiles. These tile designs are Spanish in origin and often represent the outline of foliage, flowers and leaves. The motif of the design is extracted from the internet, traced and modified on a computer, and then engraved by a machine for some hours on each of the nine panels.

As with other work, this place between distance and proximity is essential to an appreciation of Sharma’s work. Seen together as a form of installation, his work has both a compelling visuality and almost ceremonial austerity. Sharma’s panels offer a compelling attraction to be viewed in close proximity, so as to see better their elaborate design that shimmer elusively in the light. As if like the sun, the gold panels illuminate themselves. As a viewer we wish to look closely and to stand back and see it as one complete work, recalling the austere geometric designs of modernist Mexican architecture, notably Luis Barragan and his proteges such as Ricardo Legorreta. Both architects looked back and drew inspiration from pre-hispanic architecture as distinct from the heavily embellished Spanish baroque style that had dominated Mexico from the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries. The architects had used what seemingly austere, flat forms. And yet these surfaces are saturated with the colors of earth-like reds, the purples and pinks of flowers and the copper and orange of the sun. Even more pertinent are the works of the German-born Mathias Goertiz who had lived and worked in Mexico in the post-World War Two period. His gold paintings and sculpture represent an extraordinary instance of modernism in Mexico and Latin America.

The second work by Sharma are three columns, standing 1.8 meters high and 7.6 cm. Made of copper tubes, each is painted a different color: purple, crimson and a light emerald green. They are presented, separate but standing in front of the three panels. “The sculptures are very much influenced by my time in Mexico looking at columns from different civilizations including modern structures, and are basically studies in the figure and the cylinder. Sharma was also inspired by Brancusi’s seminal modernist work Endless Column or ‘Column of the Infinite,’ made of zinc and brass and completed in 1938. As a result, Sharma’s work, similar to that of his recent work, suggests an contemporary reading on the idea of infinity. Sharma uses industrial fabricators and digital technologies that are able to simulate the concept of infinity through repetition and interchangeability in the manufacture of objects or products. The idea of the model and copy is now taken one twisting step further, whereby the idea of the model or original is based on industrial technologies which enable the copy or repetition.

In quite distinct manners of approach, both Susiarlo and Sharma respond to their experience of Mexico through the use of gold. They take radically different paths, artisanal in the case of Susiarjo and industrial in relation to Sharma. Gold becomes, in a manner that resonates with both Klimt and Klein and with Goeritz, a material force that illuminates. Gold becomes for them emblematic of a cultural legacy of Mexico stretching between the two artists of Singapore, between an ancient and a modern Mexico. Beyond that, the visible materiality of gold in their work give way to its essence, the immaterial essence of its being.

— Charles Merewether, Curator